The mission of the Raleigh Historic Development Commission is to identify, preserve, protect, and promote Raleigh’s historic resources.

Our Mission

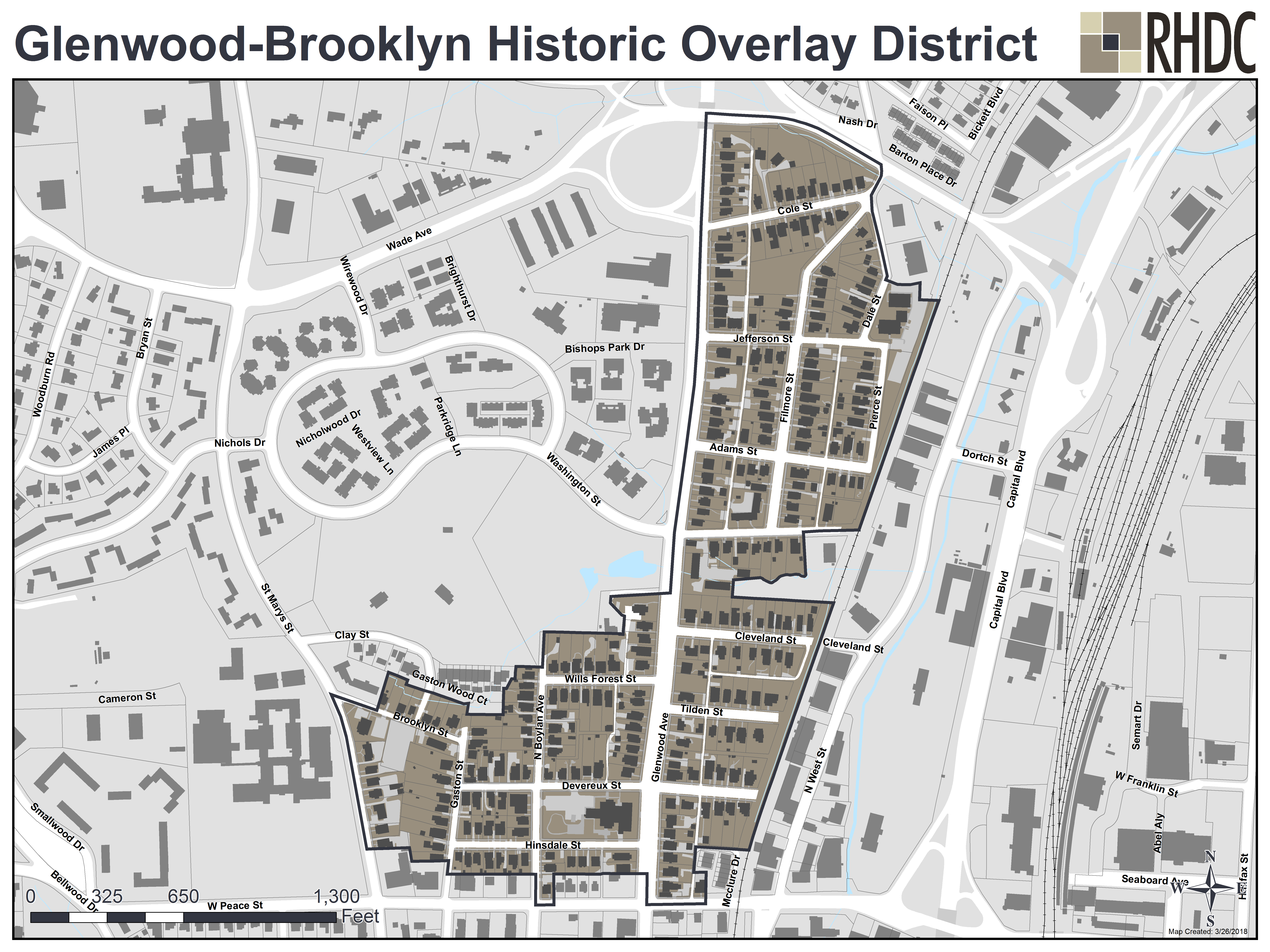

Glenwood-Brooklyn Historic District

Developed 1907-1951

An early twentieth-century streetcar suburb for working- and middle-class whites

Glenwood-Brooklyn occupies the blocks along both sides of the segment of Glenwood Avenue between Peace Street and Wade Avenue. The neighborhood marked the beginning of the suburbanization of land north of Raleigh's city limits, which ended at Johnson Street from 1857 to 1907. This coincided with the city's becoming increasingly segregated along racial and class lines, and developers intended the neighborhood to house Raleigh's growing ranks of white working- and lower-middle-class residents. They achieved this through deed restrictions that excluded African Americans and required minimum costs for houses built on the subdivided parcels. While most residents were government employees, small business owners, salespeople, or railroad employees, a few white-collar workers also chose to live in Glenwood-Brooklyn, generally in more substantial and stylish houses. Cameron Park and Boylan Heights developed around the same time as Glenwood-Brooklyn, each aimed at a different set of customers. The dominant architectural styles in the neighborhood include Queen Anne, Colonial Revival, Craftsman, and transitional styles that incorporated elements of Colonial Revival with Queen Anne or Craftsman.

History

The Glenwood Land Company incorporated in 1905 and began offering parcels in the area for residential development. Around the same time, the local streetcar system built a new line north from downtown along Glenwood Avenue, bisecting the company's land. This was hardly a coincidence: one of the three local men behind the development company was a prominent trial lawyer connected with the Raleigh Electric Company and the Carolina Power & Light Company, owners of the streetcar system.

When the first houses went up in Glenwood and Brooklyn, the Victorian-era Queen Anne style remained the most popular for residential architecture. Most Queen Annes here are restrained versions featuring asymmetrical facades, steep gable roofs, and turned and sawn porch ornament. A few also feature decorative siding. A regional house type, the Triple-A cottage (so named for its side-gabled roof with decorative third gable centered at the front of the house) also falls under the Queen Anne style and is generally a modestly ornamented house. A couple of Triple-As in the neighborhood, however, show some fanciful elements like siding that looks like fish-scale shingles (at 808 Brooklyn Street) and four-leaf gable vents (719 Gaston Street). Carpenters originally occupied both houses.

The Queen Anne style merged with the Colonial Revival, producing houses that were more symmetrical with classical detailing like fluted columns rather than turned porch posts. Around 1910, the nationally popular Craftsman style brought a proliferation of bungalows, a house type typically dressed in the Craftsman style in middle-class developments. The popularity of Craftsman bungalows left little room for regional architectural expression, particularly because so many houses of the period were mass produced and mail-ordered from Sears, Roebuck and Company or Aladdin Homes. Not all Craftsman houses in the neighborhood are bungalows, however, and a few houses, like 1200 Glenwood Avenue, show the combination of the Craftsman style with the Colonial Revival.

Map

|

|

Glenwood-Brooklyn in the 21st Century

Photo by Michael Zirkle Photography Photo by Michael Zirkle Photography |